Why we must put children first and deliver outcomes

The following is a fresh version of an opinion article written by Steve that was originally published five years ago. We are featuring it here because, not only has nothing changed in the meantime, but the recent drastic cuts to aid budgets mean that action now is more important than ever.

I believe that our failure to address wasting (acute malnutrition) is symptomatic of a profound misconception at the heart of the aid and development industry.

We misconceive our industry as something primarily benevolent: the ‘charity sector’ supplying ‘aid’ to

‘beneficiaries’ – and we fund it by selling this fallacy to the public and hence to politicians.

The facts are, however, very different.

Those suffering from wasting have rights enshrined in international law that we have a duty to fulfil. They are not passive recipients of our benevolence but active clients who must juggle multiple priorities, constraints and opportunities.

This misconception is profoundly damaging, because it focuses our attention on ourselves, our motives and our strategies, rather than the needs, rights and realities of our clients. In respect of nutrition, it cements a supply-side, central-planning mentality at the industry’s core. It perpetuates renumeration systems related to process and control of resources rather than to outcomes and impact.

Those at the centre receive large, often tax-free salaries, while those who actually deliver products and services to our clients receive very little – and are often even expected to work as volunteers.

Furthermore, the misconception incentivises excessive emphasis and investment in UN agency and NGO profiles – in order to attract funding.

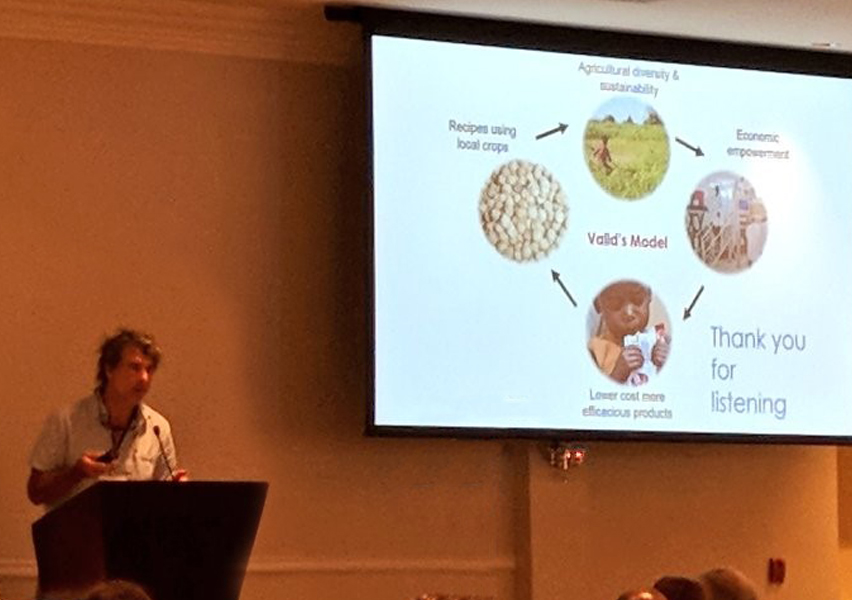

A good example of the corrosive effects of this need for profile and control of resources is the failure of the WHO and UN system to act on VALID’s development of the plant-based RUTF. Our 2017 study clearly demonstrated that the amino acid-enhanced soy maize sorghum RUTF is as effective as the standard peanut-milk RUTF in recovery and superior in the treatment of iron deficiency and anaemia, offering a viable, lower-cost, environmentally superior alternative. Yet instead of encouraging use of this recipe and finally permitting competition, the system has allowed bureaucracy, ideology and vested interests to effectively block innovation.

The inertia and failure to build on existing evidence in the face of the massive scale of unaddressed malnutrition and the suffering it causes, this is just unacceptable and morally wrong. The science on protein quality, amino acid supplementation, and micronutrient fortification together with trials on the acceptability of our plant-based RUTF, have been available for over seven years. In the interim, targets for treatment of wasting have been consistently missed by a distance, year after year.

While technocrats, policymakers, and agencies hold meetings, draft reports, and engage in endless

“harmonization exercises,” millions of children are left without treatment because there isn’t enough RUTF available. Every day that passes without action is another day where children suffer unnecessarily because of institutional inertia.

Enough is enough – after seven wasted years and millions of pounds of taxpayers’ money, acutely malnourished children need outcomes that result in impact.

Money should be going to action-oriented operational research that builds on the published, peer reviewed evidence available and delivers tangible results in treating children and demonstrating the positive outcomes at scale. It should not be directed to endless cycles of discussion papers, reviews, and framework revisions.

Ultimately, this need for profile and control of resources, also fosters risk aversion, discourages transparency and undermines innovation. It also sees profit as distasteful, precluding meaningful engagement with the private sector.

To change all this requires radically different ways of working. In particular, profound collaboration between government, the public sector and the private sector, where each plays to their respective strengths and does not engage in activities for which they are ill suited, even if this means forgoing control of resources and profile.

In almost all other walks of life, it is the private sector that delivers goods and services to people, and we must leverage its scale, capability and capacity to do this along the entire chain of service delivery, up to and including last-mile delivery to those suffering from wasting. The public sector should focus on ensuring that the services delivered meet the needs of those affected by wasting by improving targeting, transferring entitlements to ensure equitable coverage, with nobody left behind, and imposing ethical standards to prevent exploitation. The research agenda must inform us on how best to achieve this collaboration.

Enacting this change will not be easy. There are vested interests perpetuating the status quo and threats posed by increased private-sector involvement, given its history of promoting poor nutrition and exploitation. However, with sufficient will, I am sure that these vested interests can be challenged and the threats addressed.

The bottom line is that, after more than 30 years of failing to reach the vast majority of those affected by wasting, we really have no choice but to fundamentally change how we go about things.

[Dr Steve Collins, March 2025. This is an update of an article originally featured in Field Exchange issue 62, March 2020]